Michèle Friend, Professor, George Washington University

Jan. 2026

This is a very unstable and delicate moment.

As we have seen in many moments of regime change from a violent and repressive regime, a strong man steps in (or there are several successive changes in strong men that happen very rapidly). Order and stability are eventually restored. There is a honeymoon period, when promises are made, and hope returns to the people. The honeymoon lasts a while, but remember that the strong man is just that: a strong man. The promises cannot be fulfilled quickly and efficiently, because there is a lot of slow reconstruction to be done, and that takes time and patience. Two problems contribute to the fragility of the situation: the learned, and ingrained automatic reactions of distrust and deception – learned under the suppressive regime and the inherent systemic instability of the country [Emmanuel Haddad “Carnets de route en Syrie” Monde Diplomatique September 2025 pp. 1, 4, 5]. Both can contribute to local violence, mob rule, especially against minorities. We witness this in Syria today with the attacks between, and against: the Sunnis, the Druzes, the Bedouin, the Alaouite, inviting attacks from Israel… [Emmanuel Haddad “Carnets de route en Syrie” Monde Diplomatique September 2025 pp. 4, 5]. This leads to a greater show of strength from the county’s central powers.

Imagine that instead of a strong man taking power in Iran, Maryam Rajavi steps into the power vacuum with her government in exile. She does this with the institutional compass as a guide for her government and for the people. [Friend, Michèle, The Institutional Compass; Method, Use and Scope, Springer Nature, Methodos Series 18, 2022]

What does this look like.

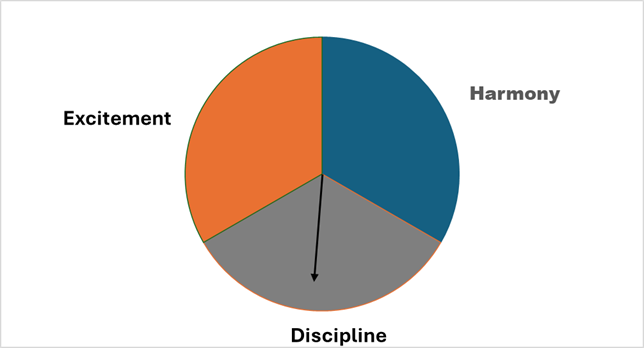

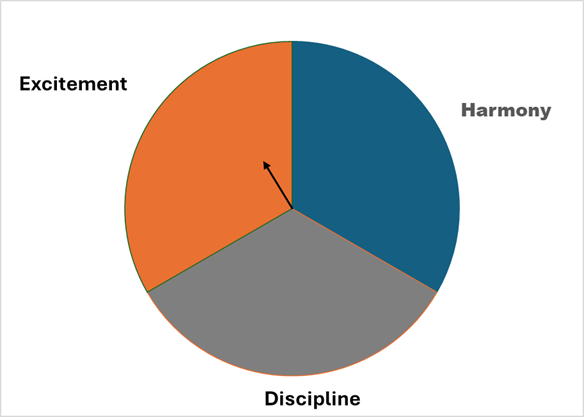

Maryam Rajavi explains to the people of Iran that her and her government are assuming power. Under the former regime, Iran, as a nation, had the following compass reading:

She explains: the compass is in the middle of discipline. This is for two sorts of reason. One is the real suffering and hardship being faced by the people of Iran: the poverty, the electricity cuts, the fear, the lack of education opportunities for women, the distrust of the governing forces, the distrust of the interpretation of the Quran… The other is the brutal suppressive forces of the (former) regime, the arrests, the executions, the torture, the support of brutal forces abroad, the development of nuclear armaments to protect Iran from attack from other countries. Both: the challenges the population faces and the reactions of the regime to hold on to power fall under discipline, and have been aggravated over the last year.

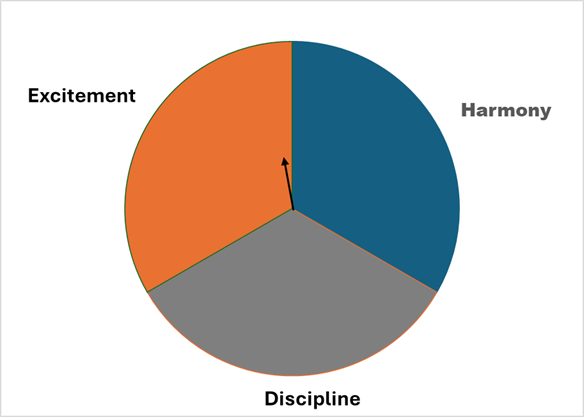

Maryam Rajavi then explains: The goal of the new government is to change Iran from the ground up. Some changes can happen quickly, such as stopping the executions, freeing political prisoners, stopping the development of nuclear weapons, allowing women back in schools and universities, change in dress code…

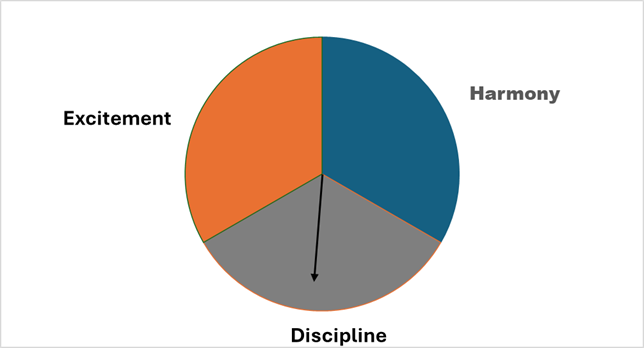

Under these quick changes, the compass reading changes. The arrow is shorter – showing the reduction in challenges and suppression in the new Iran.

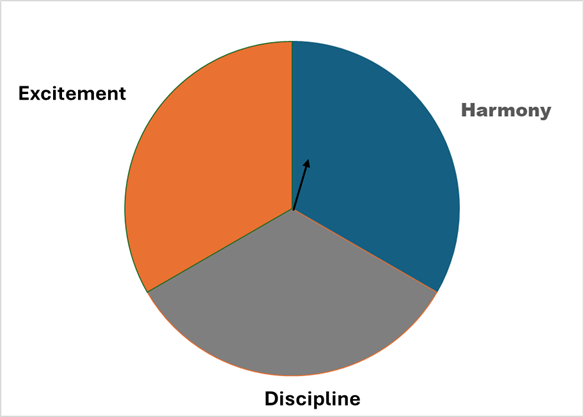

Other changes will take some time: rebuilding infrastructure, restoring electricity, repairing roads, ensuring safe drinking water for everyone, families being re-united, creating job opportunities and so on.

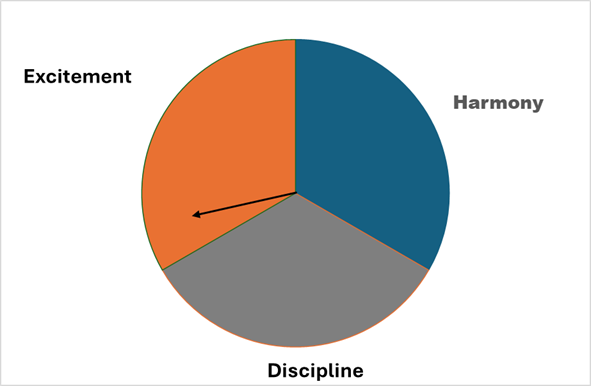

Again the arrow changes after these longer term changes are made, maybe most within a year.

The arrow is in excitement. This indicates two things. (i) Changes are being made, there is an instability because new possibilities open up. (ii) The instability, creates unknowns. Opportunities have to be seized. Who, when and how are not dictated from above but are allowed to occur spontaneously from the people – giving them agency over their future.

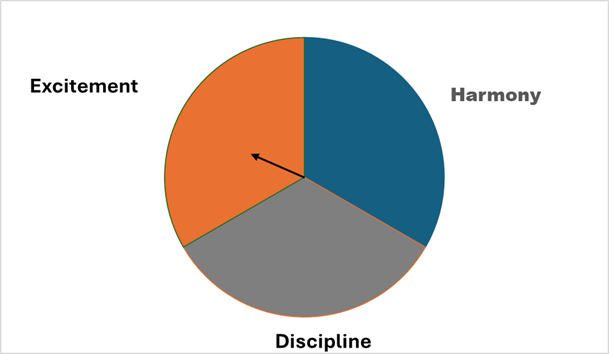

But now the real and profound changes will start: learning to trust one another, tolerance of minorities, tolerance of other religions, forgiveness for past wrongs, healing from the too many years of suffering and trauma. But piece by piece, centimetre by centimetre, the compass will change for Iran.

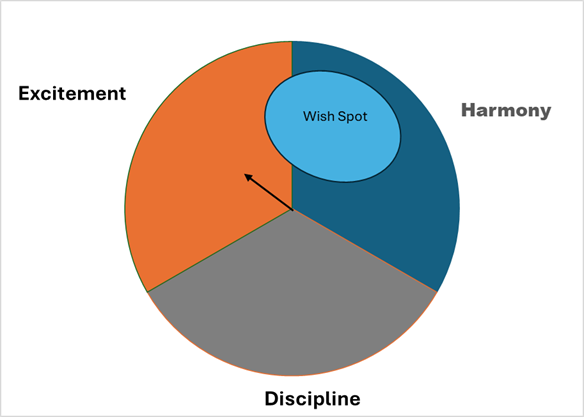

When the arrow is in harmony, this means more stability. The changes are less erratic and unpredictable and are more gradual. It is time to plan, to propose different visions of the future, reflected in several political party’s aspirations and ideologies. Some will want further change and progress – bringing the arrow back to excitement. Others will opt for more stability and support, more healing – closer the centre of harmony.

What we have just imagined was a healthy and progressive change after the fall of a violent and oppressive regime. It can be done with women leadership accompanied by the institutional compass.

Further reflections:

- Sub-regions and sub-communities could develop their own compass – representing where they lie with respect to the national compass. Some regions will be a bit ahead of the national arrow on its rotation, others will be a bit behind. If there is a sudden violent clash, then that subregion will be in discipline. The clash will influence the national arrow, and will pull it back towards discipline (since local information is a part of national information that is used to make the compass reading). Through the compass, the people can see the effect of their actions and initiatives, not only locally but nationally. In this way, the people are given agency and choice (often we call this “freedom”) but they also are asked to recognise their responsibility – in contributing to the rotation of the national arrow or hampering it.

Separate regional compasses add another dimension important for democracy – they encourage patience and trust in the governance system. If a region is a bit behind, but others are ahead in rotation of the national compass then the compasses represent the lag. The reason some regions will be ahead, and others behind is that the not all of the changes can be made effectively at the same time. There are just not enough resources available to government.

A region that is behind in the rotation can take courage. How would this be the case? Using the compass images, the public can be made to understand what it means when all changes cannot be done at the same pace in each of the regions. However, when real changes are taking place in some regions, this affects the regional and national compasses by rotating both clockwise (to a greater extent in the regional compass). A region that is behind in the rotation can take heart. When the government does step in to change the problems in a region, the local compass will change (as it did in other regions) and those local changes will have national impact. Patience and trust in the governance system are part of re-learning democracy. The compasses help with transparency.

- The compass, especially local ones, can be constructed democratically – thus re-teaching democracy through participation in governance. There are four “entry points” for the public: (1) deciding on a desired direction (within a time-frame). This is a sort-of “compass” goal setting. We call it a “wish spot” on the compass – a region on the circle where we aim to be as a region within a certain amount of time.

For example, as a community, we might have the ambition to rotate our compass 20 degrees clockwise within 6 months, to reach the edge of the wish spot. That decision can be taken from a government office, or can be taken by the public after learning about the compass and the three compass qualities and after debate. (2) The public can be asked to add data to the compass. If they make observations that an expert did not notice, the information can be verified and added. Say, for example, more children are going to school, but the teacher observes that they are sleepy and hungry, that new information can be added, since it affects how well the students will learn at school. It is not enough to increase enrolment. In order to learn, the students have to be in the right mental and physical condition. (3) The public can contribute to the analysis of the data. Different cultures and sub-cultures might have very different emotional or intellectual reactions to the same data point. For example, the national government might lift restrictions on dress codes for men and women. Some more closed religious communities might find this alarming and threatening (in discipline). More open communities will find it liberating (in excitement). Asking the community to voice their opinion on how to analyse data can be easily integrated into the methodology of compass construction. By doing so, the public learns familiarity with the compass, about differences in opinion and they learn about compromise and, therefore, democracy. (4) The public can be asked to participate in the negotiations in policy and implementation to continue the rotation of the compass reading. Individuals, or businesses, might volunteer to help with a particular data point. For example, an industrialist might provide a school bus to bring students to and from school. In return the company can advertise on the bus, showing (maybe even in “real” time) how providing the bus contributes to the regional compass rotation.

- Transparency will increase trust. It could be that out of a learned sense of distrust, that a member of the public fed wrong information to the compass constructors. He, or she, will start to see that poor quality information, or mis-information is counter-productive. It increases the instability of the arrow. Rather than following a smooth rotation, it will jump – with other counter-information. Moreover, groups that were silent because of distrust or habit, as they witness the compass changes, they will dare to make their voice heard. As Roya Johnson said to me in conversation: the mark of democracy is protection of minorities. I would add that it is listening to minorities and including their voice in the development of policy that is the real mark. We can add or update information to the compass at any time – when people are ready to share it.

Conclusion

The compass is quality-direction mirror. The accuracy increases with trust and better information. The mirror gives a distance from our individual immediate experience by representing the whole, and by representing the situation in a very abstract, albeit intuitive way. The colours on the compass are specially chosen (and can be modified to suit a particular culture). The arrow gives a reading of the quality-direction the nation is heading in at any one time (information can be updated and the subsequent arrow’s changes can be watched).

I invite you to imagine with me: Maryam Rajavi assuming power after regime fall, with the compass in hand. She, her government and the people of Iran can, through it, learn gradually, to work together towards a common goal – to bring the compass to harmony to prepare the terrain real democratic elections. The public will have started the healing process – a healing from the scars of the brutal regime. By the time the compass is in harmony, even the more wary and sceptical members of society will be participating. By the time the compass is in harmony, local conflicts will have become much less violent. Communities will support each other and work together towards an abstract goal: the rotation of the compass. They do not have to work together or agree on very much – only on the direction of rotation. All this, is what harmony means. The changes on the ground will the tangible. If there is no real change, there is no rotation. Empty promises make no difference to the compass reading.

When a violent and suppressive regime falls a strong man steps in. Maryam Rajavi is strong woman. She will be a first in recent history. She will be an example for the future in other countries. Rather than see the elation of a people spiral back because of a resurgence of tyranny and suppression (which is what a strong man is good at), we have a chance in Iran to see the elation that follows regime fall converted into a sensitive, supportive, healing and re-construction process – reconstruction of institutions, and infrastructure but also of the culture. The Iranian people are famous for their resistance, but they/ you are also famous for poetry, music, film, food, beautiful carpets and ceramics. Let these qualities return and replace the resistance. I was told recently by an Iranian woman that the Iranian people learned to transform the suppression and suffering into strength and resistance. Maryam Rajavi is asking for another great feat from the people of Iran – to transform the resistance into positive change, mutual support and tolerance.

Post-Note: you might wonder if it possible for the arrow to rotate in the other direction instead. The answer is yes. To do this would mean a lot more control over the process of change. This means a very deliberate piece by piece and more gradual change. It would require more control over the people. It is for you to decide which is the better course. One is not faster than the other, even if the distances on the compass are greater through excitement. If you want real democracy and you choose to go directly from discipline to harmony, then the path would require direct and controlled teaching of democracy – through scenario exercises, for example.