FISN Staff, December 15, 2025

On 12 December 2025, a seventh‑day memorial ceremony in Mashhad for human‑rights lawyer Khosrow Alikordi turned into a violent crackdown. Alikordi had been found dead in his office. Authorities claimed he died of a heart attack, but fellow lawyers and family members raised serious concerns—citing unusual bruising, bleeding from the mouth, and the rapid seizure of office CCTV footage. Alikordi had previously spent time in prison for defending dissidents.

The gathering, organized by Alikordi’s family, began with unified anti‑regime slogans. Suddenly, a suspicious and well‑organized group began chanting pro‑monarchy slogans, “Javid Shah” (Eternal King), and throwing stones at the organizers. They continued with anti‑MEK slogans and disrupted the ceremony. According to eyewitnesses, the same individuals were soon assisting plainclothes security forces in attacking the organizers and arresting participants.

Authorities later announced that 39 people had been arrested, including Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi.

While the incident, carried out by regime agents, was almost unanimously condemned by Iranians on social media, Reza Pahlavi, son of the deposed monarch, released a video message praising those chanting in his favor, referring to them as “people.” At the same time, the regime’s cyber apparatus launched a two‑pronged campaign: first, joined by some pro‑monarchists outside Iran, attacking individuals invited by the family to speak at the ceremony, including Narges Mohammadi, while praising Reza Pahlavi; second, promoting a false narrative that the incident was merely a dispute among regime opponents, with security forces intervening to restore order.

What are the facts:

- During the memorial, speakers raised suspicions about Alikordi’s death and criticized the regime, prompting attendees to chant anti‑regime slogans.

- The BBC reported, citing eyewitnesses, that regime plainclothes agents had infiltrated the crowd.

- The BBC also wrote that during Narges Mohammadi’s speech, a group began chanting in support of the Pahlavi family, cutting her remarks short, and that after tensions rose, security forces disrupted the ceremony and violently detained several people.

- Alikordi’s brother, who organized the memorial, expressed concerns that security forces had harassed attendees and created obstacles from the outset.

- Available video clips, including one aired by the BBC, show organizers attempting to drown out the pro‑monarchy chants by speaking louder and even invoking the name of a protester killed by the regime during the 2022 uprising.

- After the crackdown, numerous videos and eyewitness accounts circulated showing that some individuals chanting “Eternal King” later cooperated with security forces once arrests began.

- Ghazal Abdollahi, daughter of detainee Alieh Motalebzadeh, stated in an interview that those chanting pro‑Pahlavi slogans were the same people who later helped detain genuine participants.

- In a statement issued after the incident, the Jebhe Meli (National Front) association wrote: “Despite the fact that Dr. Khosro Alikordi was … a very important and influential member of this association’s Khorasan Branch, and that his history of political positions as a republican and patriotic political activist is quite clear, unfortunately, from the first days following the painful news of his death, the cyber‑monarchist movement tried to distort his image through extensive propaganda. Fortunately, there is abundant evidence which, coupled with the vigilance of you—the democracy‑seeking people—neutralized their plot. From the first moments of Dr. Alikordi’s memorial ceremony on December 12, a small but cohesive and organized group, with prior planning, began to disturb the atmosphere and disrupt the order of the ceremony by chanting royalist slogans and insulting Dr. Alikordi’s family and relatives. The disappearance of this small group from the scene at the same time as the beginning of the attack by the security‑police forces shows their full coordination with the security institutions of the Islamic Republic. Even a number of these individuals, in line with the security forces, were involved in the attack and beating of the attendees at the ceremony!!”

- The “Network of Iranians on Telegram,” based in London, wrote after the incident: “… it is necessary to clarify a fundamental and hidden fact for the public: there is basically no real, deep‑rooted, and independent current called the ‘monarchist current’ in Iranian society. What has been promoted under this label in recent years is not a genuine social force, but rather a deliberately engineered security project, directed and managed by the intelligence and security planning bodies of the regime.”

The Iranian Regime’s Textbook

The Mashhad incident became a textbook example of how a carefully injected slogan by regime agents can transform a memorial, intended to honor a human‑rights lawyer and criticize the authorities, into a spectacle that diverts attention from the central issue: opposition to clerical dictatorship.

Reza Pahlavi’s message thanking those who chanted in his support is difficult to attribute to ignorance. He has previously stated that he maintains bilateral contact with the IRGC and the Basij paramilitary force.

Slogans such as “Death to the dictator” or “Death to Khamenei” are politically unifying: they directly target the ruling structure and demand its end. By introducing pro‑monarchy slogans, the regime creates a false binary—as if the only choices are the current theocracy or a return to the previous dictatorship.

The cyber dimension: how “monarchist” accounts inside Iran were exposed

The Mashhad operation cannot be understood solely as a street event, because it was rapidly amplified online by accounts that behaved like a coordinated network.

A key development was X’s introduction of approximate location labels. In most countries, this is trivial. In Iran’s information environment, it is revealing, because it exposed that many loud “pro‑monarchy” accounts were operating from inside Iran, using government‑approved, unfiltered SIM cards, despite presenting themselves as exiles or foreign‑based activists.

This is significant because Iran is a country where dissent can lead to imprisonment, torture, or execution. Yet these accounts, using royalist flags and slogans, operate with remarkable persistence and intensity. The exposed pattern indicates coordination by intelligence and security institutions, particularly the Ministry of Intelligence and allied units, using recurring behaviors: extreme anti‑regime profanity to appear authentic, repeated claims that “Reza Pahlavi is the only alternative,” and obsessive attacks on the main organized opposition (MEK/NCRI).

The operational logic is clear: the goal is not simply to promote monarchy. The goal is to manufacture a controllable alternative that is loud enough to dominate timelines but politically ineffective on the ground—while the regime concentrates real repression on the opposition it genuinely fears.

What fake monarchist personas look like, in practice

Iran’s cyber apparatus has built thousands of accounts presenting themselves as monarchist or pro‑Reza Pahlavi to push this line at scale. These accounts fall into recurring categories rather than behaving like a natural, diverse grassroots community. All operate using government‑approved SIM cards, indicating affiliation with the Ministry of Intelligence (MOIS) or the IRGC cyber army.

Taken together, these personas manufacture the appearance of a large, unified monarchist current while concentrating their attacks on the organized opposition the regime most wants to delegitimize.

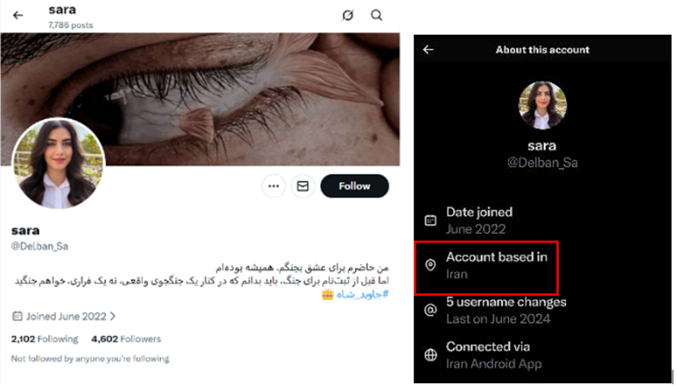

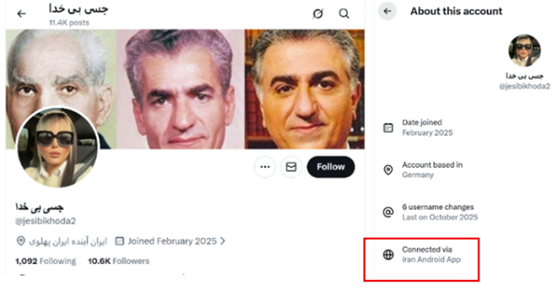

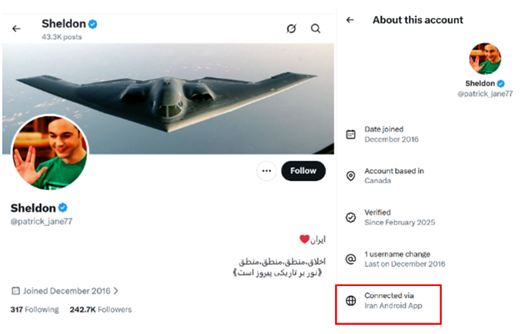

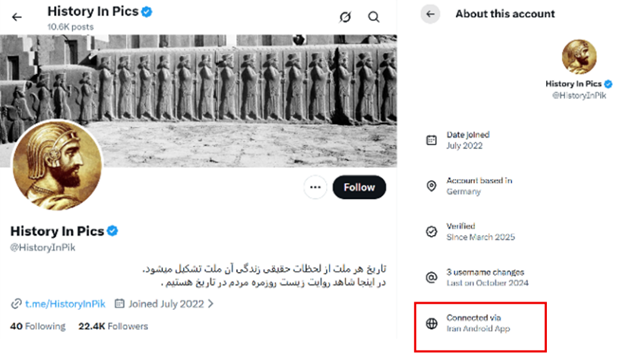

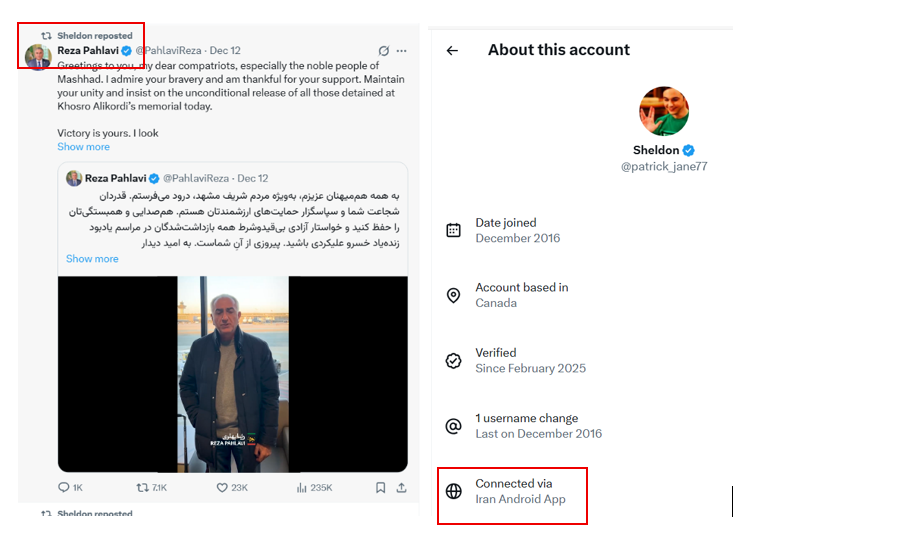

The following are examples of accounts used by the MOIS or IRGC but under different categories. If you look at the locations in each account they are connected via “Iran Android App,” while some claim to be based outside Iran.

One category runs emotional “confession” narratives—often framed as an “ex-MEK” or “former insider” story—repeating familiar smear themes in the voice of a supposedly disillusioned witness[1].

Another category performs the role of the aggressive, hyper-militarized influencer, pushing hardline pro-Pahlavi messaging and even normalizing external military action, while insisting monarchy is the only solution[2].

A third category positions itself as the calm “rational analyst” or high-following hub, using a polished tone to circulate the same political line with an air of credibility[3].

A fourth category operates nostalgia pages that flood feeds with curated images of the Pahlavi era as a lost paradise, erasing dictatorship and repression while marketing restoration as the only escape from today’s crisis[4].

How the Mashhad incident was amplified by cyber accounts posing as monarchists

After Mashhad, cyber accounts operating under monarchist branding moved quickly to frame the event as a public endorsement of Reza Pahlavi and monarchy.

A documented pattern was the broad circulation of clips from Mashhad by such accounts, including posts insisting the “Mashhad epic” should not be buried under other news. One example cited is a cyber account branding itself as “SAVAK Media,” which posted multiple clips and pushed the framing that Mashhad represented a major monarchist breakthrough. SAVAK is the name of the notorious security service under the shah dictatorship, responsible for torture and execution of political prisoners.

At the same time, these accounts widely amplified Reza Pahlavi’s own video message[5] thanking chant-givers for raising his name—reposting it at scale and presenting it as proof of domestic demand for monarchy restoration.

The unusually broad and coordinated amplification of the Mashhad clips—specifically the pro‑monarchy chants—by accounts operating with a monarchist cover is itself significant. By flooding timelines with identical footage and framing, these accounts promoted a single takeaway: that the protesters in Mashhad were “supporters of Reza Pahlavi,” rather than agents of the Ministry of Intelligence and the IRGC.

The longer pattern: “street engineering” is not new

Mashhad was not the first time monarchy slogans appeared in a suspiciously protected, operational manner.

A 25 June 2016 article in the pro‑regime daily Jomhouri Eslami described the slogan “Reza Shah, rohat shad” (“Reza Shah, rest in peace”) chanted in front of parliament. The article noted the incident was “planned,” that a group had been sent with unprecedented slogans, allowed to chant freely in front of police, and that this was the same group regularly appearing at Tehran Friday prayers and regime‑organized marches.

This is not a historical footnote. It shows that even regime‑aligned media have acknowledged cases where monarchy slogans in protest contexts were not spontaneous expressions of public will but part of a managed street presence tolerated—or enabled—by security structures.

Another example comes from 1 February 2025, when the state‑run Vatan‑e Emrooz published “Why the Monarchy in Iran Was Overthrown and Will Never Return?” While attacking monarchism, the article openly acknowledged its political utility for the regime. After describing monarchism as weak and lacking roots, it stated: “A weak and rootless movement like monarchism can actually help the survival of the Islamic Republic. This is the service the royal family provides to the Iranian people.”

What changes between 2016 and 2025 is not the tactic but the integration of street optics with a far more mature cyber ecosystem capable of mass amplification.

Capability and scale: the broader cyber infrastructure

The same location‑exposure method that revealed “monarchist” accounts inside Iran also exposed Iranian state‑linked bot activity in foreign political debates. One reported example described how a new location feature on X helped identify multiple Iranian state‑backed accounts pushing for Scotland’s independence and destabilizing the UK, with the disinformation firm Cyabra previously identifying at least 1,300 accounts backed by the IRGC’s cyber warfare unit in that context, including the use of VPN infrastructure to disguise locations.

The point is not Scotland; it is capacity. A state capable of maintaining coordinated botnets and persona farms for foreign influence can just as easily build domestic networks posing as monarchists, flood hashtags, and shape the narrative after events like Mashhad.

Mashhad, therefore, is not merely a dispute over slogans. It is evidence—on the ground and online—of a deliberate strategy: manufacture a “safe” opposition optic, amplify it through regime‑linked cyber networks, and use the resulting confusion to suppress genuine opponents.