The Psychology of Collective Trauma, Political Anger, and Institutional Architecture in Contemporary Iran

By: Iraj Abedini, Psychologist, Sweden

February 21, 2026

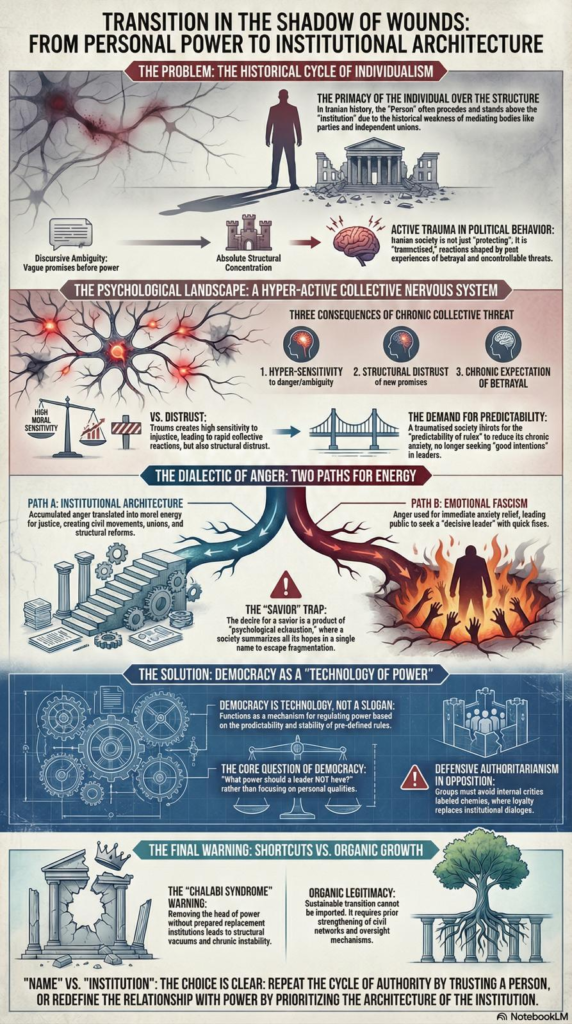

The issue facing contemporary Iran is not merely a crisis of a political structure; it is a foundational crisis in the “relationship between society and power.” For more than a century, from the Constitutional Revolution to the present, the central struggle has not been over the replacement of individuals, but over transforming the “logic of legitimacy.” The recurring questions have been these: Where does power originate? How is it restrained? What mechanism keeps it accountable? And most critically, which institution holds the authority to remove it?

If these questions remain alive, it is because they have not found a durable institutional answer. In the absence of institutional solutions, society has repeatedly resorted to personal ones.

1. The Primacy of the Individual over Structure: A Historical Cycle

In modern Iranian history, the “individual” has often emerged before the “institution” and stood above it. This primacy has not merely been a cultural trait; it has also resulted from the historical weakness of intermediary institutions: stable political parties, independent unions, free media, professional associations, and mechanisms for distributing power. Whenever these mediating institutions have been weak, the resulting vacuum has been filled by a single figure.

The experience of 1979 demonstrated how “discursive ambiguity” in the pre-power phase can, after consolidation, transform into “absolute structural concentration.” Initial promises of freedom and participation were rewritten in the absence of predefined and agreed-upon rules. This was not merely a political shift; it left a wound in the collective memory that continues to function as an “active trauma” shaping political behavior in Iran.

A society that has once experienced the rewriting of promises after the consolidation of power becomes sensitive to any new ambiguity. This sensitivity is not the product of inherent pessimism; it is the product of experience.

2. A Hyperactive Collective Nervous System

Iran today, before being merely a protesting society, is a traumatized one. Decades of repression, war, debilitating sanctions, widespread executions, systematic blockage of future opportunities, and the suppression of protests have created a condition of “chronic and uncontrollable threat.”

In trauma psychology, such conditions produce a hyperactive nervous system. At the collective level, this state manifests in three enduring patterns:

Heightened sensitivity to threat: intense reactions to ambiguity or shifts in position.

Structural distrust: difficulty accepting new promises.

Expectation of betrayal: anticipation of repeated historical deception.

Yet this is not the whole picture. The same hyperactivation can also generate “heightened moral sensitivity.” A traumatized society is not only distrustful; it is also more sensitive to injustice. Rapid reactions to corruption, discrimination, or violence are part of this heightened awareness. Thus, this condition is both impairing and capacity-building.

In such a context, discursive fluctuation by a political figure between republicanism, parliamentary monarchy, or a referendum is not perceived as mere tactical diversity. For a traumatized mind, it may signal the “dangerous fluidity of power.” Society is no longer seeking “good intentions”; it longs for “predictability of rules.”

3. The Dialectic of Anger: From Organization to Emotional Fascism

Accumulated anger in Iran is the product of years of humiliation, discrimination, and blockage. Anger is a mobilizing and ambivalent emotion.

In its first trajectory, anger can transform into moral energy for justice and “institutional architecture.” Historical examples show that organized anger can lead to the formation of unions, civil movements, and structural reforms. In this path, anger is translated into law and civic networks.

In its second trajectory, anger can become a mechanism for immediate anxiety reduction. Under chronic insecurity, institutional complexity feels exhausting. Legal processes appear slow. The collective mind seeks certainty. A decisive leader becomes appealing because he promises rapid relief. This phenomenon can be described as “emotional fascism”: the concentration of power as a temporary anesthetic for pain.

Importantly, this tendency does not necessarily arise from a desire for authoritarianism; it is often a mechanism for reducing anxiety. If left unexamined, however, it can reproduce the very pattern it sought to replace.

4. Normative Stability and the Technology of Democracy

Democracy is not a heartfelt wish or a moral slogan; it is a technology for regulating power. This technology rests on the predictability and stability of rules. In democratic leadership theory, “behavioral predictability” is a prerequisite for institutional trust.

If a political figure fluctuates on foundational issues such as the form of governance or the boundary with violence, a message of “normative instability” is conveyed. In a society marked by “replacement trauma”—the fear that the next regime may be worse—such fluctuation is interpreted as a readiness to rewrite rules once power is attained.

Democracy begins with this question: “What powers must the leader not possess?” If mechanisms of removal, oversight, and division of power are not defined before transfer, power will define the rules after consolidation.

5. The Desire for a Savior: The Psychological Economy of Exhaustion

The desire for a “savior” in contemporary Iran does not arise from intellectual simplicity; it arises from psychological exhaustion. A society whose hopes have repeatedly collapsed becomes prone to condense all aspirations into a single “name.” A figure can temporarily reduce anxiety, create a sense of direction, and contain fragmentation.

Yet history has shown that reducing anxiety at the cost of concentrated power produces greater long-term costs. Democracy is not built upon unconditional trust in an individual, but upon the prior limitation of that individual.

6. Defensive Authoritarianism within the Opposition

Authoritarianism is not solely a feature of established regimes. Under threat, opposition movements may also drift toward “defensive authoritarianism.” This occurs when, in the name of preserving unity, internal critics are quickly labeled as “enemies.” Personal loyalty replaces institutional dialogue.

Personalization of politics, intense polarization, and the reduction of structural complexity to the will of a single individual are signs of this tendency. If a political culture is built upon personal loyalty, political transition will merely change actors, not the rules of the game.

7. The Chalabi Syndrome and the Necessity of Organic Legitimacy

International experiences, including what is referred to as the “Chalabi syndrome,” demonstrate that removing the head of power without preparing replacement institutions leads to structural vacuum and chronic instability. Imported legitimacy or military shortcuts cannot substitute for organic collective learning.

Sustainable transition occurs only when civil networks, political parties, professional institutions, and oversight mechanisms have already been strengthened.

Conclusion: The Choice Between “Name” or “Institution”

Iran’s younger generation stands at the intersection of anger and global awareness. This generation understands that sustainable freedom is the product of divided power, transparency of legitimacy, institutionalized mechanisms of removal, and behavioral stability of leaders.

Healing Iran’s wounded spirit, much like trauma treatment at the individual level, requires rebuilding trust, defining stable rules, and tolerating complexity. Democracy is the fruit of institutional patience, not immediate emotional release.

The choice before us is clear: either we once again entrust power to a “person” and remain within the cycle of authoritarian repetition, or by prioritizing the “institution,” we fundamentally redefine society’s relationship with power.

Sustainable transition does not emerge from the shortcut of charisma, but from the patient architecture of institutions.