March 11, 2022 (Esfand 20, 1400) — Germany

Dr. Aziz Fooladvand Sociologist and Scholar of Islamic Studies

Translation from Farsi version: https://freeiransn.com/%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%87%db%8c%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%b3%db%8c%d8%a7%d8%b3%db%8c-%d8%b3%d9%84%d8%b7%d9%86%d8%aa-%d8%a7%d8%b2-%d9%be%d8%b3%d8%b1%d9%90-%d8%b1%d9%8e%d8%b9-%d8%aa%d8%a7-%d9%88%d9%84%db%8c-%d9%81%d9%82/

Divine Origins: The Creed of the Ancient Kings

“I am Darius… King of Kings… the representative of Ahura Mazda.”

“By the will of Ahura Mazda, I am king. Ahura Mazda bestowed kingship upon me.”

“Ahura Mazda granted me this kingship. Ahura Mazda aided me in gaining it.”

“All that I have done, I have done by the will of Ahura Mazda.”

Darius the Great says: “Whatever happened, it was all by the will of Ahura Mazda. Ahura Mazda aided me in all my endeavors. May Ahura Mazda protect me, my royal house, and this country from harm.”

Such was the worldview of our ancient ancestors. The inscriptions that have reached us from antiquity bear witness to this perspective. It could be said that these inscriptions encapsulate the political theology of kingship itself: the essence of royal legitimacy is divine and celestial. It is by the will of Ahura Mazda that the king ascends the throne. The subject has no will of his own—he is only to obey and submit.

This article is an inquiry into the nature of kingship and the identity of the king. It seeks to trace the roots and symbols of this institution. The institution of Iranian kingship is the remnant of a distant past. Understanding this ancient political thought is a necessity for our present time. For ages, this old institution has been the bedrock of social change in our society. To consider this institution is to seek solutions to many conundrums; without critical reason and an understanding of its essence, foundations, and doctrines, pluralism, justice, and liberty are placed in grave jeopardy.

Critical reason, and with it the values of democracy and parliamentarianism, were sacrificed on the altar of “Iranian kingship.” Sovereignty—rooted in divine mandate—was seen as heavenly and unearthly, eternal like the gods. It was a divine gift, preserved by the celestial radiance (farr-e-izadi). It did not originate “from here” but “from beyond.”

“Your throne, the crown of the heavens; your crown, the divine radiance.” (Khaqani)

The celestial radiance was inherited, and thus kingship was deemed everlasting:

“It will continue among the male descendants [of the king] from generation to generation.”

The very core of royal ideology is “Long live the King!” The king is eternal, and it is this eternity that preserves Iran. The endurance of Iran is thus bound to the immortality of the monarch. The veneration of the sovereign is the precondition of patriotism. This institution thrives on veneration and worship; the royal court becomes its sanctum. Palaces and grand halls are the embodiment of royal theology and imperial grandeur. The court is the ceremonial center of veneration for the King of Kings. Courtiers encircle the “Pivot of the Universe.” Proximity to the sovereign increases their stature. In the seclusion of the royal chamber, the affairs of the realm were determined.

Ra, the Sun God: Divine Right and Sacred Genealogy

“Ra” was the supreme sun god of ancient Egypt, believed to have created himself out of the primordial waters, to have risen from the first blue lotus, from the first mounds and chaotic oceans. He is eternal and the creator of all being, ruler of the heavens, sovereign over earth. From his tears were created men and women, the Nile, the beasts, the herds, the seasons, the plants. The Pharaoh is his son—his absolute viceroy—granted the “absolute sovereignty” by Ra, the sun god. Ra is the ruler of all gods, just as the Pharaoh, his son, is “King of Kings.” His power pervades all; his majesty is ever-present.

Tradition ordained that every Egyptian king was to be recognized as the son of the great god Amun. Thus, Hatshepsut, daughter of Thutmose I, declared herself a man and of divine descent, composing a genealogy that recounted:

“Amun, wrapped in clouds of perfume, descended upon her mother Ahmasi and was welcomed, and when Hatshepsut was born, it was declared that the full splendor and power of the god would reside within her.”

(Will Durant, Vol. 1, p. 231)

Such faith-based, fabricated genealogies became the foundation for the legitimacy of kingship and clerical authority. In our own era, even Aryamehr invoked “revelations,” “miracles,” and the “Hidden Imam” to buttress his own sacred genealogy. These “revelations” of kingship would be inherited by the Supreme Jurist, who—upon setting foot in the material world—cried the name of Ali.

The Celestial Diadem: Symbolic Foundations of Kingship

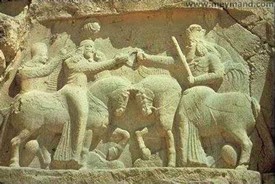

This stone relief symbolically conveys the “religion” of kingship: Ardashir Babakan and Ahura Mazda, mounted on horseback, face each other. The first Sassanian king (on the right) receives the royal diadem from Ahura Mazda himself. He is the chosen of Ahura Mazda, his authority is transcendent. He is to rule the world as the vicegerent of Ahura Mazda. His reign is eternal. The relief is meant to communicate that Ardashir’s sovereignty is divinely ordained, his immortality a “divine gift.” His commands are the words of the divine; his essence is unearthly. His legitimacy is the divine radiance (farr), and the name “Ardashir” itself means “holy king.” He played a central role in advancing the ideology of kingship in our land. The king is the chosen of God, the guardian of the realm. Obedience and veneration of the king are sacred duties. The sovereign’s political order is a cosmic order.

To disrespect the king is to offend the gods and disrupt the harmony of the cosmos—an unforgivable crime. Not everyone is worthy of this divine gift. A people known as “subjects” are, within the king’s domain, bound to suffer the king’s tyranny (Dehkhoda, Proverbs and Sayings). Subjects are not to decide their own affairs or the fate of the kingdom; they require a caretaker and a shepherd. The king is a “nurturer of subjects,” raising them to be fattened for tribute and taxes.

“Subjects are like unweaned children.” (Marzban-Nameh)

They are minors, bound in obedience to their guardian.

Evil and the Enemy

In the above relief, two further symbols appear: under the hoof of Ahura Mazda’s horse, the demon Ahriman is vanquished; beneath Ardashir’s steed lies his defeated enemy, Ardavan, the last Parthian king. The relief articulates the “political theology of kingship” through symbols: the triumph of Ahura Mazda over Ahriman, and the king’s victory over his adversary. The enemy is Ahriman—his equal in wickedness—deserving of nothing but humiliation and subjugation. The enemy must prostrate himself; the foe of the sovereign is he who refuses submission, who rebels. He is an outsider, “enemy of king and country,” a “heretic,” a “counter-revolutionary,” and an “enemy of the order.” The relief openly depicts the fusion of sovereign and deity: Ahura Mazda over Ahriman, and the king over the enemies of kingship. This entanglement of religion and government is of ancient lineage. The clergy learned it from the kings. The doctrine of the Supreme Jurist is Khomeini’s adaptation of the political theology of kingship: the source of political authority is not the people, but the gods.

The cosmic struggle between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman is mirrored on earth in the realm of politics. The king’s religion is one of duality: good and evil, right and wrong, believer and infidel, barbarian and civilized, pure and impure, divine and demonic, subject and king. The king enforces his faith; imposition and discrimination are its very essence. The monarchy is inherently religious and thus despotic; it knows not tolerance or forbearance. Its terms—discrimination and coercion—ignite envy, animosity, and malice. Hatred for the “other” is its order of the day.

The history of monarchy is also a history of hatred’s proliferation. The king is ever in conflict with the “other.” His creed is superior; others must submit. With his creed, the king propagates a despotic disposition:

“People follow the religion of their kings.”

The king instills a culture of coercion, intolerance, hatred, flattery, vice, and hypocrisy. The culture of injustice, plunder, ambition, amorality, aristocratic affectation, and despotism are the creations of tyrants—whether king or supreme jurist.

“Revelations and Manifestations”

A long journey separates antiquity from the year 1973. In that year, “His Imperial Majesty” unveiled his most secret mysteries in an interview with Oriana Fallaci, the renowned Italian journalist. The Shah shared with us his “mystical” experience, confessing that,

“…despite everything, I am never truly alone, because a force unseen by others accompanies me. A mystical force.”

This experience was not limited to mystical company; he also received “religious messages” from the unseen. He had, for 49 years, kept this secret:

“Since I was five, I have lived with God, but it was from the time when I received revelations.”

It seems that divine grace, from time to time, is bestowed upon God’s chosen ones even in childhood. The Shah translates the divine radiance of ancient times into the idiom of his own era:

“Twice in my childhood I received revelations, once at five and again at six. The first time, I saw the Hidden Imam—who according to our faith is concealed until the day he will return to save the world… I know this because I saw him, not in a dream but in reality, physical reality, do you understand? I saw him, that’s all. The person who was with me did not see him, nor was anyone but me supposed to, because… ah, I fear you may not understand… My revelations were miracles that saved the country. My reign saved the country because God was close to me…”

The substance of these “revelations” is borrowed from the inscriptions of antiquity. The “Muslim king” ousts the ancient monarch, and “miracle” takes the place of divine radiance; the Hidden Imam replaces Ahura Mazda or Ra as the king’s patron. The illegitimate monarch requires celestial legitimacy. Deception is the custom of both king and cleric. When the world narrows, the heavens are vast and full of “manifestations,” divine endorsements, and heavenly grace. The Shah, in 1973, faces terror and repression, absolute power and universal hatred. The preservation of the throne without “divine intervention” is unthinkable. Perhaps the angels of “revelation and manifestation” may come to his aid. Immersed in mystical rapture, the Shah asserts:

“Here it is necessary and right that some people be executed. Here, pity is futile.”

Thus, through the theology of kingship, he sees himself as the shadow of God: the king is God’s representative, male, guardian of faith, one of the chosen, inherently superior, the very source of power, grace, and mercy.

“Sovereignty is a trust conferred upon him as a divine gift.”

For “great civilization,” he needs neither rational citizens nor pluralism, democratic values, rationality, legality, diversity, parliamentarianism, separation of powers, or republic. “Revelations” and the “Hidden Imam” will provide all.

So it was that Mohammad Reza acquired Aryan divine radiance and ascended to the rank of god-king, Shahanshah Aryamehr. The “essence” of the king is sacred—purer, nobler, cleaner, otherworldly, and supreme.

(From a circular by Hirad, Chief of the Royal Court, referring to Prime Ministerial Directive No. 27724-15/7/1344 [1965])

From 1970, Mohammad Reza became enamored with the title “His Imperial Majesty Mohammad Reza Pahlavi Aryamehr, King of Kings of Iran.” By royal command, the Chief of the Royal Court sent instructions to all ministries. Words and titles encapsulate the religious essence and political theology of the institution of monarchy: the king and kingship are sacred. The king is the incarnation of both religious and political power; as God’s chosen, obedience to his commands is a sacred, personal obligation. Rebellion is sin and, in law, a crime.

The king is a semi-mythical being, for he rules two realms: earth and heaven. The sacred tradition of kingship demanded that the king be half divine. Thus, in the political theology of monarchy, when the king is killed, dies, is deposed, proves incompetent or corrupt, or flees, no blame attaches to him. In any case, he is “pure and unsullied.” After him, kingship continues among his male heirs. In other words, Ahura Mazda or the “Lord of the Age” bestows kingship upon his chosen man. Individual merit is meaningless—the “royal bloodline” is all. The “good genes” bear the institution.

The acquisition of divine grace and the status of God’s shadow could also be achieved by the sword. The history of kings is full of clashing swords, intrigue, beheadings, blinding, and murder of rivals. The grace and radiance of God went to the victor; divine radiance could be won by cunning and slaughter. The victor imagined himself the chosen one and was exalted to the highest station. The land was governed for centuries on the foundation of this divine gift and God’s shadow.

The Connecting Link

Let us pose a question: Is the institution of sacral monarchy in the modern era a suitable framework for the realization of democratic values? Can the ancient institution of kingship be a vessel for human rights in our time? Was society’s break with monarchy in 1979 not, in fact, the historical failure of the religious essence of kingship? Our historical experience answers clearly: the ancient theocratic monarchy was reproduced in the clerical order. In our age, the Pahlavi dynasty became the link between theocratic kingship and the Supreme Jurist. The heritage of antiquity was bequeathed from monarchy to the institution of the clergy. The “divine gift” was transferred from “His Imperial Majesty” to the “Supreme Jurist.” The Pahlavis fulfilled their historic mission in preserving and transmitting this religious institution to the clerics.

From antiquity to modernity, the institution of kingship in our land has zealously preserved its celestial, unearthly essence.

The doctrine of the Supreme Jurist arose within the very discourse of kingship. The trinity of “God – King – Nation” metamorphosed into “God, Quran, Khomeini—hail to Khomeini!” There is no difference between the two sanctuaries: the royal court and the Supreme Leader’s household are both celestial institutions, sanctuaries of “holiness.” The household of the Supreme Jurist is no different from the king’s court. When the king-centered, theocratic monarchy collapsed, a new order arose in its place—centered on the Supreme Jurist.

Social Schizophrenia

Modern humanity has outgrown the cramped ceiling of the “sacred essence of kingship.” Critical reason and rationality have challenged every tradition. The old religious monarchy and clerical guardianship provide no room for freedom and liberty of thought. The despotism of kingship and the rigidity of clerical rule are no longer suitable answers. The grand project of liberty cannot be confined to the narrow vessels of monarchy and clericalism. We must prepare a new vessel. One cannot speak of the separation of religion and state while clinging to the ideology of theocratic kingship. Nor can one proclaim the “gates of civilization” while remaining ensnared in the trinity of “God, King, Nation.” One cannot attack the Supreme Jurist in bold terms only to seek refuge in the sacred tradition of monarchy. Breaking with the monarchy (rooted in religious essence) is the necessary precondition for breaking with the guardianship of the jurist.

For the devotees of this political order, the necessity of a king is an article of faith, dignity, and ideology—just as the Supreme Jurist is for Khomeini’s worldview. The king and the Supreme Jurist are not rational or political matters, but religious and faith-based ones. Perhaps this is why adherents of both monarchy and the clerical order are caught in the grip of their own emotions. This erroneous approach and belief are signs of social schizophrenia.

The process of critiquing and breaking with tradition is fraught with tension and psychological crisis. Critical reason, however, is rare. Critiquing oneself and one’s own lineage is a transformative act, demanding both passion and courage. “Break” requires transformation: a change in character, thought, and self-understanding—a transformation of faith. In this upheaval, the rebellious human being becomes the helmsman of transformation. One ensnared in tradition views himself as an object—valueless and captive. Tradition encloses his entire being. His behavior, norms, and thought are confined. He is property, possessed by tradition. He is discontented, objectified, helpless, and submissive—subject to the dominion of tradition.

Breaking with long-standing norms and traditions precipitates an identity crisis. Enthusiasts for monarchic and clerical orders, in the process of “breaking,” are confronted with intense crises: legitimacy crisis, psychological crisis, and intellectual crisis. Thus, they cannot sever themselves from the grip of despotic traditions. The keepers of tombs and custodians of old customs remain in mourning, seemingly slower than their own times. Yet, when the great flood arrives, all graves are washed away. The classical belief persists stubbornly: the king and sultan are “the shadow of God”; he is the guardian, and obedience to him is obligatory. This outlook—and the accompanying political thought—are remnants of the archaic idealism of ancient times. The survival of the ideal of the king—the Mazdean king—in modernity owes much to the doctrine of Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri. In his view, “Prophethood and kingship” are complementary; the weakening of either one leads to the cessation of Islam (Treatise on the Illegitimacy of Constitutionalism). He grieved the undermining of the “Sultan, Refuge of Islam,” and would not tolerate the “

foolish attacks against the Muslim sovereign” by constitutionalists. For him, kingship was the executive arm of the sharia; the monarchy was the “executive authority for the laws of Islam.” Should anyone dare to rebel and contemplate the downfall of the “Islamic state,” patience would not be permissible. This is the same delirious obsession with kingship and clerical despotism—a suffocating fanaticism that cannot meet the needs of our time. This culture is the residue of an era of human immaturity and naivety.

But what is to be done with the dreadful spiritual poverty, the intellectual and literary degeneration of king-worshippers and imitators of the Supreme Jurist? They dwell in the depths of ignorance and humiliation. Only a great leap can heal this pain: the new human—rebellious, critical, filled with self-sacrifice and transformed by a “leap of faith”—a human striving upward, ever eager to give and sacrifice.

“He always sacrifices himself.” (Nietzsche)

This superior human has subdued the ideology of “I first.” The doctrine of “can and must” is his guide.

The New Human, Critical Reason

In the modern age, a new human has stepped onto the stage: rebellious, critical, pragmatic, and bold. This new human has introduced a kind of knowledge to the world, whereby all existence is, before his mind, an object—conquered, subdued, obedient. He leaps beyond time, turning his back on the creeds of notables, elders, and monarchs. The world is tamed before him. His mind is the “subject”; existence, in all its manifestations, becomes the object of his knowledge. “Subject” versus “object.” All must yield to his will and bow before him: “And they prostrated” (Qur’an 2:34). All domains of knowledge—natural, human, psychological—become his province. He creates, even conquering blind fate. The boundaries of knowledge cannot constrain him. The new human tears through the shells of absolutism, dogmatism, and traditionalism. His language is rational and mathematical. Reason is his reference point; he does not revere the mythic images and idioms of antiquity for understanding existence. He has new perspectives and creeds, new tools, mechanisms, political, social, cultural, artistic, and militant methods. No domain is beyond his systematic, purposeful inquiry. He conquers the domains of psyche and faith. Ambitious, his modern mind is rebellious. He looks at the world creatively, systematically, re-examining all phenomena, events, behaviors, and ideas. The stature of this human owes nothing to heaven or gods; he is an earnest actor on earth, triumphant over himself, in command of his own destiny. His starting point is the questioning mind; he is not a worshipper, but a seeker of wisdom, and thus ready for the greatest sacrifice. Reason attests to his capacity for sacrifice. He is captive neither to nature nor the gods, neither to kings nor clerics, nor to his own instincts. He is freed from the alienating relations of commodity society. As a free, sovereign, knowing, and wise will, he asserts his mastery, imposing himself on the world, shattering the bonds of tradition, creating a new order and salvation. In the pre-modern world, in antiquity, reason was yet unchained by tradition and habit, not the foundation of existence. Mythic mentality prevailed; society was ruled by gods, kings, and priests. Reason must liberate itself. Reason must overcome its own bonds—environmental, traditional, customary, emotional, royal, and clerical. This is a difficult and arduous path. In antiquity, “human existence” meant something quite different, and the realm of thought was severely limited.

Nostalgia and Totem

In the modern age, traces of longing for the ideal monarchy may yet survive in some layers of society. Yet this presence is not the product of critical thinking or an understanding of the foundations of freedom and democracy; it is a sign of attachment—or rather bondage—to antiquity, a nostalgic feeling. Nostalgia is vague, a connection to the past, providing comfort and solace. Nostalgia tames the restless, rebellious, questioning soul. It is an opiate, an escape from inquiry, from iconoclasm, from deciding to change oneself and the world—this world, the world to come. Nostalgia is a kind of poverty: poverty of thought, poverty of courage, of sacrifice, the courage to grapple with the present.

According to Immanuel Kant, poverty gives rise to nostalgia. Wealth and social success drive this feeling from the human heart.

Nostalgia is evoked by scenes, flavors, melodies, memories, and scents of childhood. The attraction to kingship recalls the childhood awe of monarchs. The worship of kings is the residue of humanity’s earliest worship. It is a form of totemism: the totems of early tribes—eagle, bear, otter in North America, bull in Greece and Egypt, cow in India and Africa and Scandinavia, buffalo in southern India, kangaroo in Australia. The “sacred totem” of monarchy is a remnant of this belief system.

Nostalgia is mourning for the dead. Those who long for monarchy mourn at the tombs; those attached to the totem of kings suffer the same pain as those attached to the totem of the Supreme Jurist—the pain of loss.

The Necessity of the Age

Transcending the religious essence of sovereignty is the necessity of our era. Only through a persistent and rigorous critique—an unending struggle with the dual cults of theocratic monarchy and clericalism—can we rationalize our political order. The establishment of a democratic order, worthy of the new human, depends on a break with the despotism of monarchy and clericalism. No other course is trustworthy. The worship of kings and imitation of clerics befit not the new human.

The break with these two institutions is the first condition of “solidarity.”

Dr. Aziz Fooladvand

March 11, 2022 (Esfand 20, 1400), Germany