Dr. Hossein Jahansouz, Biochemist and a Leading Scientist and Industry Executive in the United States for Over Three Decades

Abstract. Iran’s steel sector, anchored by Mobarakeh Steel Company (MSC), is a cautionary tale of systemic corruption, politicized governance, and energy mismanagement. This paper integrates parliamentary investigations [1][2], investigative journalism [3], trade data [4][5], and academic analyses [6][7], with updated industry data and market context. It details how procurement fraud, IRGC patronage, and misallocation of resources crippled this strategic industry. The consequences span Iran’s economy, labor force, and foreign trade. The paper concludes with reforms to restore integrity, efficiency, and competitiveness, although the author does not believe that the current Iranian government is neither interested nor capable of reform.

1. Introduction and Historical Context

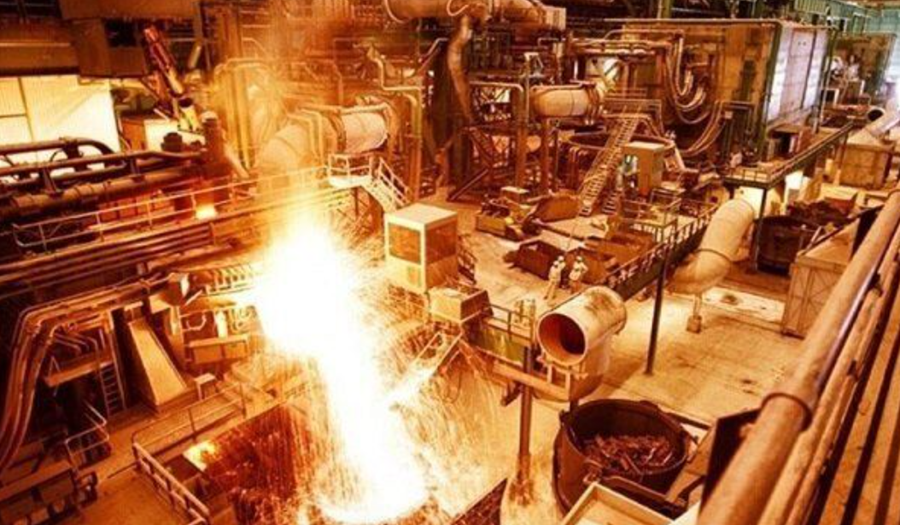

Iran’s steel industry was envisioned as a pillar of national industrial sovereignty, with MSC intended to match world-class producers in both output and quality [4]. Its location in Isfahan provided access to raw materials, skilled labor, and transport infrastructure. In the 2000s, MSC’s rising production and exports appeared to validate these ambitions.

Beneath the surface, structural weaknesses persisted. Governance relied on opaque decision-making, politicized appointments, and noncompetitive contracting. Modernization stalled due to underinvestment. International sanctions restricted access to advanced technologies, financing, and spare parts [7]. These conditions undermined productivity and efficiency.

Between 2018 and 2021, the combination of poor governance and sanction-driven opacity created fertile ground for large-scale corruption [1][3]. This culminated in one of the most significant industrial scandals in the country’s history. The scandal’s emergence also exposed how deeply political priorities outweighed industrial needs in Iran’s economic planning.

2. The Mobarakeh Steel Scandal: Origins, Scale, and Political Fallout

The August 2022 parliamentary report documented over $3 billion in irregular transactions [1][2]. More than 90 cases involved shell companies, phantom contracts, and inflated invoices for goods never delivered. Payments flowed to IRGC-linked companies, religious seminaries, and state-controlled media outlets [6]. These revelations showed that MSC’s resources were being used to maintain political alliances rather than invest in modernization or efficiency.

The Tehran Stock Exchange suspended MSC shares, an extraordinary measure highlighting the severity of the allegations [2]. International coverage portrayed the scandal as a symbol of Iran’s wider governance failures [3]. Observers noted that MSC’s downfall reflected a deeper pattern of state-linked companies being treated as political instruments.

Inside Iran, debates intensified over the IRGC’s economic role. Reformists and conservatives blamed one another, while independent economists warned that such corruption undermined both investor confidence and industrial capacity. International analysts pointed out that MSC’s collapse eroded Iran’s competitiveness in the global steel market.

Public outrage spread to factory floors. Unpaid workers in Isfahan protested, demanding wages and accountability [1]. These demonstrations became rallying points for broader critiques of the regime’s economic management, drawing attention to the structural flaws in how strategic industries are run.

3. Procurement Fraud and the IRGC’s Patronage Economy

MSC’s procurement processes resembled those in other IRGC-controlled firms [6][7]. Khatam al-Anbiya Construction Headquarters (KAA) received major contracts without competitive bidding [6]. Inflated costs and low-quality deliverables were common. Many contracts contained confidentiality clauses that blocked internal scrutiny.

Invoices were sometimes inflated by 400%, with excess funds directed to political allies or IRGC projects [3][6]. The lack of transparency created an environment where even basic cost verification was impossible. Sanctions increased reliance on intermediaries abroad, making financial flows harder to trace [7].

Oversight bodies encountered interference, while auditors faced intimidation. Whistleblowers were silenced, reinforcing a culture where personal loyalty outweighed public accountability. This culture ensured that corruption persisted even when it was widely known.

4. Militarization of Industrial Governance

Management at MSC and other strategic firms has increasingly been filled by IRGC veterans [6][7]. Their priorities reflected regime security goals more than operational performance. This culture discouraged foreign technology partnerships and limited R&D investment. Industrial decision-making was driven by political loyalty rather than operational efficiency.

The militarized governance model prioritized political loyalty over efficiency. In many cases, suppliers were chosen for their connections, not their capabilities. International investors remained cautious, wary of secondary sanctions linked to IRGC affiliations [7].

Similar patterns appear in petrochemical and infrastructure sectors [6]. These industries also suffer from centralized decision-making, chronic delays, and weak cost controls. This has fostered a systemic problem where national industries become tools for political consolidation rather than engines for economic growth.

5. Production Volatility, Energy Shortages, and 2024–2025 Data Trends

World Steel Association data shows Iran’s crude steel output declined by 6.7% in 2024–2025 [4]. The sector’s heavy dependence on natural gas for Direct Reduced Iron production makes it vulnerable to winter gas shortages [8]. Summer electricity rationing further disrupts operations. Extended outages have also harmed export schedules, damaging Iran’s reputation with foreign buyers.

Government policy prioritizes residential power needs during peak demand [5][8]. This forces shutdowns at industrial facilities, raising unit costs and reducing quality. Frequent restarts of furnaces also damage equipment and lead to higher maintenance costs.

Without diversifying energy sources and upgrading efficiency, the sector will continue to underperform. Analysts warn that capacity utilization rates could drop further if current policies persist [8]. The situation is aggravated by outdated infrastructure and limited investment in alternative energy solutions.

6. Downstream and Trade Impacts

Unreliable steel supply disrupts downstream sectors such as construction, automotive, and heavy manufacturing [5]. Delays and cost overruns are now routine. Export partners in Asia and Africa have scaled back orders due to delivery uncertainties and payment complications [7]. Even long-term buyers have sought alternative suppliers.

Loss of credibility affects Iran’s regional competitiveness. Domestic mega-projects, including urban transport and industrial parks, struggle with material shortages and inflated prices. These problems ripple across the economy, slowing job creation and raising inflation.

Iran’s inability to meet compliance and certification standards excludes it from premium global markets [7]. This limits diversification and growth. The long-term result is a steel sector that is more isolated internationally and more vulnerable to internal inefficiencies.

7. Social Fallout: Labor, Communities, and Public Trust

Labor unrest has grown as layoffs, wage arrears, and unsafe conditions persist [1]. Protests in Isfahan, Khuzestan, and Hormozgan illustrate the link between workplace grievances and political dissatisfaction. Workers have expressed frustration that while billions were stolen, they struggle to meet basic needs.

Communities tied to steel production face shrinking incomes, business closures, and outmigration of skilled labor [1][5]. These changes undermine local economies and deepen regional inequalities. The social contract between state enterprises and workers has broken down.

Public perception of MSC has shifted from a symbol of industrial achievement to a case study in corruption and mismanagement. Restoring trust will require visible reforms and consistent delivery on worker protections.

8. Pathways to Reform

This author believes that the current Iranian government is neither interested in nor capable of undertaking genuine reform. The entrenched political and economic structures benefit too greatly from the status quo. Nevertheless, it is important to outline what meaningful reforms would require.

Governance reforms: Remove security agencies from industrial management. Implement merit-based hiring and competitive procurement [6][7]. These changes should be paired with independent oversight bodies that report publicly on performance.

Procurement transparency: Use public e-procurement systems and beneficial ownership registries [6]. This would make it harder for shell companies to siphon funds.

Energy strategy: Diversify energy sources, modernize infrastructure, and guarantee supply to key industries [8]. Introducing renewable energy into the steel production chain could reduce vulnerability to seasonal shortages.

Trade compliance: Align with international anti-money laundering and sanctions rules [7]. This would open the door to re-entering premium export markets.

International engagement: Build trust with foreign investors through transparent, accountable governance [7]. International partnerships could provide access to modern technology and management practices.

Reforms must be sustained and monitored to prevent backsliding. Without them, the sector will remain stagnant, and the same structural flaws will continue to undermine performance.

9. Conclusion

MSC’s decline reflects the broader flaws in Iran’s political economy: militarization, corruption, and lack of transparency [6][7]. The scandal’s scale shows how the combination of political capture and economic mismanagement can destroy even a strategically important industry. Structural reform is the only way to revive the steel sector and restore public trust. Without such change, Iran’s steel industry risks permanent decline.

10.References

[1] RFE/RL. “Corruption Investigation Rocks Iran’s Largest Steelmaker.” Aug. 23, 2022. https://www.rferl.org/a/iran-mobarekeh-steel-corruption-investigation/32001399.html

[2] Iran International. “Tehran Exchange Suspends Largest Steel Maker For Corruption.” Aug. 21, 2022. https://www.iranintl.com/en/202208219449

[3] OCCRP. “Iran’s Largest Steel Company Caught in Billion-Dollar Corruption Scandal.” Aug. 24, 2022. https://www.occrp.org/en/news/irans-largest-steel-company-caught-in-billion-dollar-corruption-scandal

[4] World Steel Association. World Steel in Figures 2025. June 4, 2025. https://worldsteel.org/wp-content/uploads/World-Steel-in-Figures-2025-1.pdf

[5] Tehran Times. “Iran’s Steel Production Sees Modest Growth in 2024.” Jan. 26, 2025. https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/509074/Iran-s-steel-production-sees-modest-growth-in-2024-reaching

[6] UANI. “Khatam al-Anbiya.” Profile page, accessed Aug. 14, 2025.

https://www.unitedagainstnucleariran.com/ideological-expansion/khatam-al-anbyia

[7] Iran Watch. “Khatam-al Anbiya Construction Headquarters.” Updated Dec. 20, 2023.

https://www.iranwatch.org/iranian-entities/khatam-al-anbiya-construction-headquarters-kaa

[8] RealClearEnergy. “Iran’s Energy Crisis.” Jan. 20, 2025. https://www.realclearenergy.org/articles/2025/01/20/irans_energy_crisis_1085448.html