Dr. Sofey Saidi (PhD International Relations), Geneva School of Diplomacy & International Relations

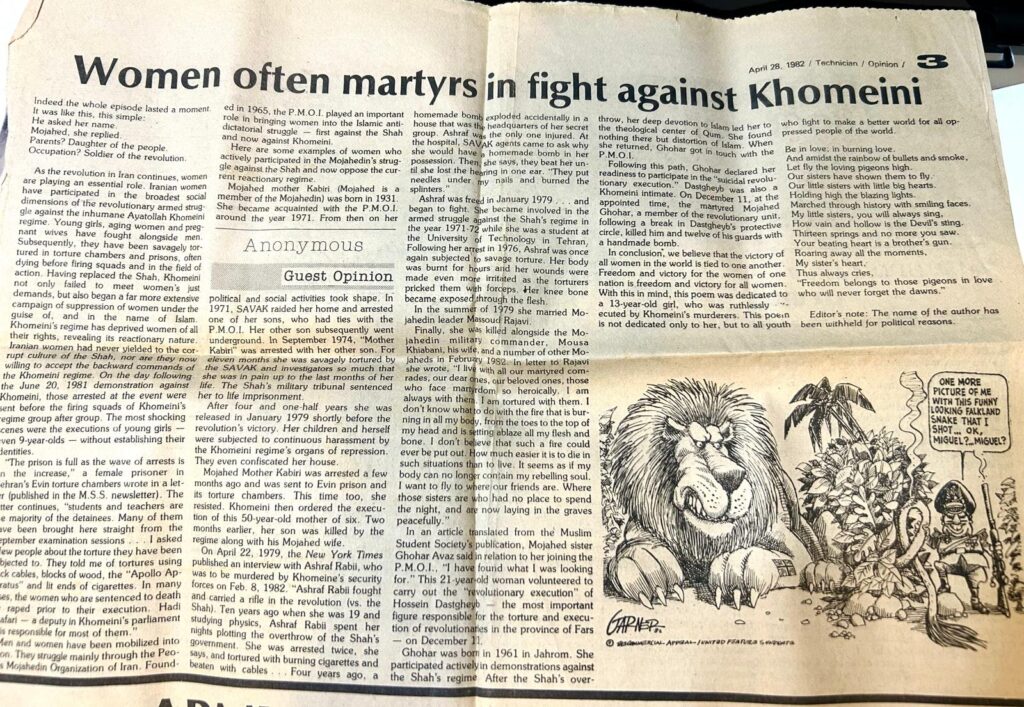

Reflecting on “Women Often Martyrs in Fight Against Khomeini” (1982–2024)

When I first wrote this article in 1982 for my university’s newspaper, I was a young student compelled to document the extraordinary sacrifices of Iranian women. The women who defied tyranny under both the Shah and Khomeini. Iran was then only three years removed from the revolution, but the dream of freedom had already been suffocated in prisons, executions, and enforced silence. What struck me then—and still resonates today—was that repression in Iran was not new. The Shah’s monarchy had already perfected a machinery of torture, censorship, and secret police. Khomeini’s theocracy merely inherited and intensified that apparatus.

Four decades later, the pattern remains: women continue to lead the longest-standing resistance against dictatorship, still offering the clearest democratic alternative for Iran’s future.

In 1982, my article “Women Often Martyrs in Fight Against Khomeini” chronicled how women—just three years after the revolution—were confronting a regime that had betrayed their hopes. Their courage was met with brutal repression: imprisonment, torture, and execution.

Yet, out of this brutality arose one of the most enduring organized resistance movements of modern history: the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI/MEK). Unlike scattered uprisings, the Mojahedin built the infrastructure of an organized resistance—networks, leadership, and vision—that enabled them to survive massacres, executions, and relentless demonization campaigns.

The persistence of this movement demonstrates something vital: repression may silence individuals, but organization sustains a nation’s hope.

Today, under the leadership of Maryam Rajavi, the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) embodies this continuity. More than 50 percent of its leadership are women—an extraordinary reality in a region too often marked by gender exclusion. This is not symbolic representation; it is a conscious strategy ensuring that women, who have borne the brunt of dictatorship, also lead the struggle for freedom.

Rajavi’s Ten-Point Plan outlines a democratic future for Iran: gender equality, secular governance, abolition of the death penalty, separation of religion and state, and adherence to international human rights. It is not a manifesto of theory, but a roadmap forged through decades of sacrifice.

One detail I could not safely name in 1982 deserves recognition now. Both the opening and closing poems of my original article were the work of Hamid Assadian, one of the Resistance’s greatest literary voices. At the time, he was still in Iran, facing the threat of imprisonment and execution, which forced me to omit his name.

Assadian was more than a poet—he was a researcher, novelist, and playwright whose words fused analysis with cultural imagination. His poetry distilled the essence of the struggle: love, sacrifice, defiance, and hope. In exile, his writings were part of the cultural heartbeat of the Resistance, preserving memory and fueling determination.

In 1985, I traveled to Managua for the fifth anniversary of the Nicaraguan revolution. At that moment, the sense of liberation was palpable. Yet decades later, the Sandinista experiment collapsed under the weight of its own failures—chiefly the absence of cohesive organization and principled leadership. The ideals of freedom and justice that had inspired their revolution against Somoza’s dictatorship could not survive without structure, accountability, and unwavering commitment to democratic principles.

This experience reinforced for me a truth I had already witnessed about Iran: without disciplined organization and visionary leadership, even the most passionate movements for freedom can falter. The Iranian Resistance endures precisely because it has safeguarded both.

Reflecting on this piece forty- three years later, I see continuity where once I only saw urgency. The Iranian people’s desire for freedom has endured through two dictatorships, and their organized resistance—led by women, sustained by sacrifice, and inspired by vision—remains the clearest hope for democratic change.

The martyrs I wrote about in 1982 are not forgotten. Their struggle lives on in the determination of new generations. The Resistance’s survival through decades of repression—when so many other movements worldwide collapsed—underscores a lesson history has taught me from Tehran to Managua: freedom cannot survive on hope alone. It must be anchored in organization, leadership, and an unbreakable commitment to justice.

And that is why, after four decades and now a participant in this Resistance, I still believe: Iran’s future belongs not to its dictators, but to its people—and above all, to its women, who have carried the torch of resistance across generations.